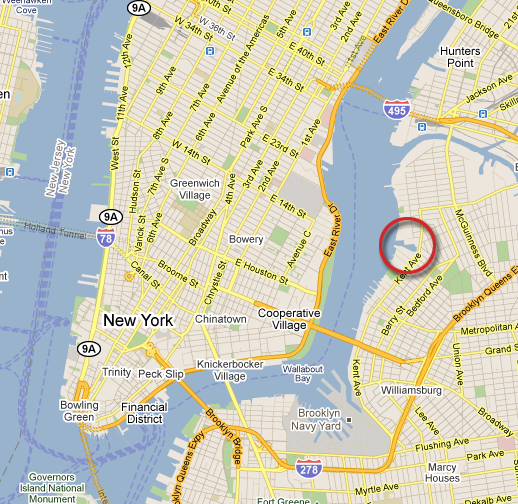

This movie started from a very basic premise: what is that little tiny inlet of water I see on every map of New York?

It’s the Bushwick Inlet. Why is it called ‘Bushwick,’ if it’s at the intersection of Greenpoint and Williamsburg? Well, the whole area was called ‘Bushwick’ long ago – and the inlet was actually a creek that flowed far inland, creating the marshy, aqueous terrain that the neighborhood was known for.

Bushwick, and, more particularly, the north-western portion of Brooklyn, was known for its arable land and extensive waterways. But the Dutch heritage of the European settlers, combined with the desire to cash in on real estate in a booming city, gradually led to the draining of the marshes, the straightening of the meandering paths of the waterways – and, in the case of the Bushwick Creek, filling it in completely.

It didn’t happen overnight. Bushwick Creek was a major thoroughfare for Brooklyn businesses to hawk their wares across the East River in Manhattan, as well as a popular locale for swimming and boating. As the city grew in population, its industrial and residential waste dramatically increased in quantity, and the logic of the time was to dump it into the waterways and let it wash out to sea.

That was a mistake, at least in Brooklyn. (In Manhattan, the raw sewage pipes dumped out underneath the piers, gradually expanding the girth of the island with ‘landfill,’ which helped expand the city’s boundaries). The Bushwick Creek became a major eyesore, and was known for its stench. Eventually, the trash became so cumbersome that boats could no longer traverse the creek, and proposals were given to fill it in completely to gain land and build a park. During this time, residents were actively encouraged to dump their trash into the creek, and landfill finished off the job. What remains is a tiny inlet off the East River – the marshland of the creek is now McCarren Park, and the entire length of the creek itself is filled in.

Strange, huh? If there was a creek in your backyard and it was being over-polluted, would you ever consider filling it in? It seems like in today’s age, a major effort would be made to recover the creek to its natural state, as is happening with the Newtown Creek (and the Gowanus Canal, although that one is mostly man-made). But such was the logic of the time. In fact, such thinking permeated all aspects of expansion and industry, leading NW Brooklyn to be one of the most thoroughly polluted areas in the city – which is saying a lot.

Yet these days, Greenpoint and Williamsburg are thriving communities in the midst of massive gentrification – old factories are being replaced by high-rise condos all along the waterfront. So who cares about some old filled-in creek?

Well, for one thing, it seems we didn’t do a very good job of filling it in.

When ground was broken for new high-rise condominiums at Roebling and N. 11th Street in Williamsburg, oil was seen visibly bubbling up to the surface, leading to the nickname ‘The Roebling Oil Field.’ Strange, huh? At first, the oil was blamed on a ruptured underground tank, making the flow seem temporary. But that theory was later discounted, in part because the oil kept on flowing. So where did it come from?

According to Ward Dennis, it’s coming from the Bushwick Creek: the building is right above its original path. The East River is a tidal strait, and the mouth of the creek at the East River housed Charles Pratt’s Astral Oil Works – so a creek filled in with trash over a century ago may still be acting as a conduit for all kinds of pollution throughout the area. In fact, the original path of the creek winds its way through no less than four locations on the state’s Environmental Site Remediation List.

Of course, New York has completely redesigned its original landscape to befit a city of its density – ‘Manahatta’ means ‘Island of Hills,’ after all – but little is known of the potential environmental ramifications of all of the trash and sewage used as landfill, or the hydrology of now-underground waterways filled in centuries ago. The area around Bushwick Creek was home to many Manufactured Gas Plants (MGPs) – without a doubt the most toxic of all industry, in regards to its effects on soil, water and air pollution. In addition to contaminating the surrounding area with all kinds of toxic substances, MGPs leech out a material called ‘coal tar,’ a by-product of the gas creation process that is highly toxic to humans. There were hundreds (maybe thousands) of MGPs in the New York City area at the turn of the Century; one of the largest in Brooklyn, the Williamsburg Gas Works, was right at the mouth of the Bushwick Creek.

Coal tar can be toxic to humans in three ways: inhalation, contaminated water, and ingestion. The chances of inhalation are slim, unless you’re working in the contaminated soil, or you’re in a contained building directly on top of it. Contaminated water is a major issue at other MGP sites (there were over 30,000 MGPs in America), but not in New York, as we ‘import’ our water from the Catskills nowadays. So, as long as we don’t eat the soil, we should be fine, right?

Well, not exactly. For one thing, for MGP locations (as well as the sites of their holding tanks) are often active industrial sites these days. The location of the storage tanks for the Williamsburg Gas Works is now a palette company that employs dozens of workers every day, working directly on top of the dirt, or working inside. Either is dangerous: MGP toxicity exposure is greater in a contained area, but working in direct contact with the dirt is also quite bad. Why is this company working here without any safeguards? And why are there new high-end residential condominiums across the street?

Well, that’s Williamsburg: build the condo first, ask questions later – or, better yet, never at all.

In addition to pollution concerns, there is an element of class warfare in relation to the fight for the future of the waterfront. When Mayor Bloomberg’s administration re-zoned the entire Williamsburg and Greenpoint waterfronts, the plan was clearly targeted to real estate developers with deep pockets and an interest in waterfront realty that was inevitably going to increase in value. What was initially lost in this plan was the ability of average New Yorkers to gain access to the waterfront at all: if a line of new condominiums blocks access to the water, would it become exclusive to the affluent citizens who could afford such fancy high-rise condos?

Local citizens fought for both low-income housing in the new developments, as well as waterfront access for the public. So now, you can’t see Manhattan from inland Williamsburg or Greenpoint, due to the new high-rises – but you can go hang out on the edge of the East River, in the shadows of the new towers.

The solution to this problem is, of course, a public park. Bushwick Inlet park – the single largest allotment of public land in the Mayor’s plan for the area – will allow visitors to go right up to the water (you don’t want to go in the East River) without being on private land. This is the somewhat predictable compromise in a F.I.R.E. economy: allowing millionaires to live on the waterfront, and the rest of us, no longer with a Manhattan view, to visit occasionally.

And that’s the nature of New York, or any large American city these days. At the expense of history, and with blatant disregard for environmental safety, the city creates a waterfront vision that benefits real estate developers and their rich clients, and only the local residents pay a price. We are creating layers of history – strata of the past, I guess. We rarely dig down into this past, but when we do, we find things such as African burial grounds, boats from the 18th Century, and oil flowing freely along an underground stream.

Perhaps this is merely the inevitable march of progress on the city. New York is perpetually changing, making it harder and harder to look at its past – but at a certain point, the city must stop repeating the same mistakes. The level of industrial waste and MGP-effluvia flowing under our neighborhoods should leave some wondering if it’s a good idea to, say, raise kids here, or buy a house in Northeast Greenpoint. No one has an interest in endangering the public, but real estate goes up so quickly these days, with so many millions of dollars at risk upon any delay, that one may want to think twice about living full-time in an apartment complex like the ‘Roebling Oil Field.’ Those in possession of this knowledge are often the ones most interested in hiding it from the public. This movie aims to change that.

Click here to watch the movie now.

July 3rd, 2011 at 11:09 pm

Wow! ThNK YOU FOR INVESTIGATING THIS. IT SEEMS LIKE SOMETHING SO IMPORTANT. THANKS AND GOOD LUCK!

August 5th, 2011 at 4:58 pm

McCarren Park is located in Greenpoint not Williamsburg.

August 5th, 2011 at 5:19 pm

Thanks! Of course, at the time the park was created, it was a little bit of both Williamsburg and Greenpoint:

February 7th, 2013 at 12:44 pm

Exactly how much time did it acquire you to write “Bushwick Creek: The Movie”?

It contains a good deal of really good knowledge. With thanks -Maple

February 7th, 2013 at 1:54 pm

It took about a year, but only because it’s hard to line up interviews with so many busy people. Other than gaining info from knowledgeable folks, I spent a day or two at the Brooklyn Museum researching maps, and used the Brooklyn Eagle’s extensive online archive (and some NY Times articles too).

December 18th, 2015 at 7:57 pm

Link to picture of Kent Avenue Bridge over Bushwick Creek, June 15, 1910:

http://nycma.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~13~13~785638~114107:nyb_v1_37?qvq=q:bushwick%2Bcreek;lc:RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~7~7,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~31~31,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~22~22,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~33~33,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~29~29,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~30~30,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~32~32,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~13~13,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~17~17,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~6~6,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~8~8,RECORDSPHOTOUNITBRO~4~4,RECORDSPHOTOUNITBRK~1~1,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAN~2~2,RECORDSPHOTOUNITQUE~1~1,RECORDSPHOTOUNITSTA~1~1,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~36~36,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~20~20,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~35~35,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~16~16,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~1~1,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~5~5,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~2~2,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~6~6,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~15~15,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~24~24,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~9~9,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~19~19,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~21~21,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~34~34,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~5~5,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~9~9,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~4~4,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~26~26,RECORDSPHOTOUNITMAY~3~3,RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~25~25&mi=0&trs=1